By Laura López González

In a post-truth world, this false belief researcher offers a simple three-step recipe for building trust and finding common ground. Hint: It starts by recognizing you might be wrong.

America has a misinformation problem. It’s in our news feeds, on our social media timelines, and at our kitchen tables. It’s driving wedges between friends and family — and sharp political divides.

UC San Francisco Psychiatry Professor Joseph Pierre, MD, has spent decades working with patients with delusions and mental illness, while also writing about delusion-like beliefs held by otherwise healthy people. In his new book, False: How Mistrust, Disinformation, and Motivated Reasoning Make Us Believe Things that Aren’t True. Pierre reveals how many of us are more susceptible than we think to false beliefs. We wanted to find out why — and ask the million-dollar question: What should you do when a loved one falls for misinformation?

What drove you to write a book about false beliefs now?

Occasionally, you’ll see headlines like, “America is Suffering from Mass Delusion,” or likening some people to “cult members” based on political beliefs. Popular portrayals of those who believe misinformation often imply there’s something wrong with the individual: They’re mentally ill, they’re stupid, they’re “brainwashed.”

In my book, I emphasize that it’s not just individual factors that are to blame for false beliefs. It’s the world we live in today. It’s the way we interact with information.

How do cognitive “quirks” or biases set us up to believe false information?

Broadly, cognitive biases are automatic unconscious types of thinking that tend to result in beliefs that conflict with reality. There are hundreds of cognitive biases, but I like to emphasize two related concepts: confirmation bias and, although not technically a cognitive bias, motivated reasoning.

Confirmation bias describes our tendency to select information that confirms our existing beliefs. Conversely, when we encounter information that contradicts what we want to believe, we tend to swipe past it and ignore it.

The related process of motivated reasoning happens when we engage with information and — based on our ideological or group affiliations — we trust information sources that support our ideological views and discount those that don’t.

Why would our brains betray us like this?

The cognitive biases I mentioned are short cuts that seem to act in service of allowing us to feel good about ourselves and to think that we’re always right, and so we never have to admit that we’re wrong. That seems to be part of their purpose, whether it’s evolutionary or not.

You’ve coined the term “confirmation bias on steroids” to explain our present moment. What do you mean?

When I was a kid in the ’70s, searching for information, I’d go to the library and pick out a book or consult an encyclopedia. Today, we get on our cell phones and type a question into a search engine, but search and social media algorithms are programmed to give us information based on our previous searches. If you and I conduct a Google search using the exact same terms, we’ll get different results based on our previous experiences.

Confirmation bias is something our brains do: We’re already biased towards information that we want to see, but the algorithms we use to search for information today are also geared towards reinforcing the things we believe — it’s a double whammy. So that’s why, I argue in my book, that today we’re susceptible to “confirmation bias on steroids.”

You created a simple framework for people to understand what contributes to and drives false beliefs. Talk us through it.

There are so many reasons why individuals cling to false beliefs. I wanted to develop an overarching, universal way of thinking about it, inspired by my work as a clinician. I came up with the 3M model that involves mistrust, misinformation, and motivated reasoning.

| 3M Model | |

|---|---|

| Mistrust |

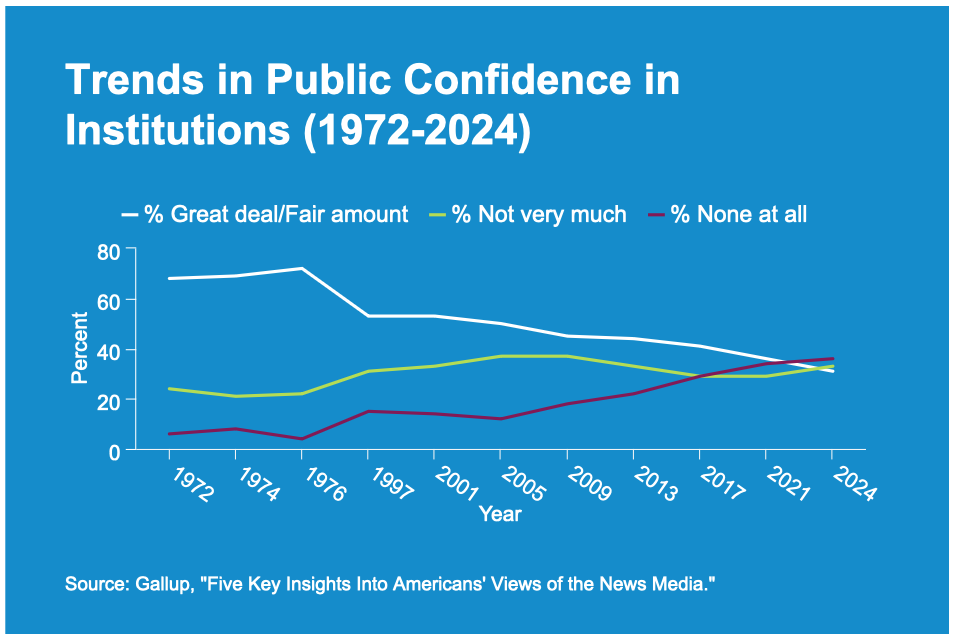

I’m specifically referring to mistrust in mainstream sources of information, institutions of authority, and scientific expertise. Many people who embrace false beliefs often do so because they distrust authoritative sources of information. We live in an era where people disagree on the facts, and that’s not because people are stupid or brainwashed; it’s because we trust different information sources. If we mistrust authoritative sources of information, we become susceptible to various forms of misinformation. |

| Misinformation | When we mistrust authoritative sources of information, we become susceptible to various forms of misinformation. Misinformation is much more accessible and challenging to discern than in the past. Over the past 50 years, there’s been deregulation and expansion of cable TV stations, as well as the internet boom. Our media landscape has transformed — we have a myriad of information at the click of a button, but unreliable sources of information are now situated right beside reliable ones. That has often made it difficult and sometimes even impossible for some of us to tell the difference. |

| Motivated reasoning |

We are vulnerable to believing things that aren’t true due to mistrust and misinformation, but what predicts whether you believe misinformation or not? A lot of that has to do with our social identities and the groups that we subscribe to. For instance, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, confidence in vaccines wasn’t that different across political parties. These days, based on our affiliation with political or other ideological groups, there’s a fairly clearly sense of what we are or are not supposed to believe. |

What do people often get wrong about engaging with those espousing misinformation?

People ask me all the time, “How should I engage with my difficult uncle at the next family dinner?”

My first response is, what’s your agenda? They’ll often reply: “I want to tell him how wrong-headed he is.”

If that’s the case, sorry, you’re not likely to succeed. You can’t start from that place.

Then, how do you respond to people who believe misinformation?

It depends on the situation. I try to avoid confronting people on social media. I don’t think it takes us forward. Likewise, Thanksgiving dinner is generally not a space where I want to engage like that.

Now, if we’re talking about me as a physician in the clinic or even engaging with a friend where we disagree, I think follow the 3M model.

You can’t try to convince people that they’re wrong and that you’re right if you don’t start from a place of mutual understanding and trust. In that vein, I might start a conversation by saying:

“I’m so interested in what you believe. Tell me more about this.”

If I hear something that seems unusual or is divergent from what I believe, I might ask:

“Well, tell me why you believe that?” or “Where did you hear about that?”

After listening to their answer, I might add: “Oh, that’s interesting.” Why? Because it’s a compassionate way of listening and signaling that I genuinely want to understand.

So, winning over your difficult uncle at Thanksgiving is a long game?

Absolutely. The bottom line: We’re in an era in which people don’t agree about the facts, and that’s not because people are “crazy” or “stupid.” It’s really because we rely on different informational sources.

If we’re going to crawl back from that, we have to build trust, and we have to understand what people’s sources are.

What’s your prescription for the present “post-truth” world?

The path to steer away from false beliefs and closer to the truth, both as individuals and as a society, involves three strategies:

- Intellectual humility: We acknowledge we could be wrong.

- Cognitive flexibility: Not only do we acknowledge we could be wrong, but we’re willing to listen to other perspectives and possibly change our minds.

- Analytical thinking: This doesn’t mean being particularly smart. It means instead of jumping to conclusions, we pause and ask, “Is this news headline right?” Maybe it’s wrong. Perhaps I should, for instance, read the article before retweeting. It’s really about understanding our own vulnerability to false belief before we can then try to engage with other people.