By Dana Smith and Nicholas Roznovsky

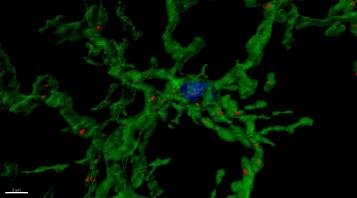

Digital rendering of a microglial cell [Courtesy Molofsky Lab]

Between the ages of two and four, the human brain has an estimated one quadrillion synapses – the electrical connections between neurons. As we age, pruning out extraneous synapses enables existing ones to run more efficiently and is just as important as forming new cellular connections. An imbalance between synapse formation and removal has been linked to developmental psychiatric disorders, including autism and schizophrenia.

Glial cells, such as astrocytes and microglia, are commonly thought of as the support cells of the brain, but emerging evidence suggests they have important roles in synapse formation and pruning. Glial cells are also instrumental in the brain’s immune system, and immune signals communicate with the brain through receptors located on these cells. UC San Francisco assistant professor of psychiatry Anna Victoria Molofsky, MD, PhD, and assistant professor of laboratory medicine Ari Molofsky, MD, PhD, are researching how these two processes occur normally during brain development in the hope of determining how subtle shifts in balance lead to neurodevelopmental disorders.

In a new study published online Feb. 1, 2018, in Science, a team of researchers led by the Molofskys has shown that an immune signal named interleukin 33 (IL-33) plays a crucial role in allowing the brain to maintain the optimal number of synapses during the development of the central nervous system (CNS).

“Most of the psychiatric diseases that we deal with are in some form or another neurodevelopmental, whether it's early childhood experiences that increase your propensity to develop depression and anxiety later in life or whether it's abnormalities in brain development that lead to autism and schizophrenia,” explained Anna Molofsky, a member of the UCSF Weill Institute of Neurosciences and practicing psychiatrist who is trained as a cell and molecular biologist.

“The immune system is not just for infections, but also shapes normal tissue development and remodeling” noted Ari Molofsky, who is a practicing pathologist and trained as an immunologist. “This study shows that the immune system also sculpts the developing brain.”

A key to synapse population regulation

Before now, the exact role of IL-33 and similar cytokines – substances secreted to have an effect on cells by the immune system – in the process of normal synapse formation and pruning has been unclear. The Molofskys and their colleagues have uncovered that IL-33 is produced by developing astrocytes and in turn signals microglia to promote increased synaptic pruning, in effect acting as a regulator of the number of synapses created and eliminated throughout typical CNS development.

As the brain matures, IL-33 production is increased, thereby enabling more pruning of synapses. Furthermore, additional study conducted by the group connected IL-33 deficiency with a significant reduction in microglia-induced pruning. Taken together, the results demonstrate that the immune system can thus influence brain development by affecting glial cells that control synapse remodeling.

As a result, Anna Molofsky believes that glial cells and the brain’s immune system may be a better target than neurons to intervene during childhood development.

“It's very hard to target neuronal wiring, but it's much easier to target glia, which are fundamentally very plastic cells,” she noted. “In terms of designing treatments for neurodevelopmental diseases, it's important to think about the cell type that's the most malleable, and the immune system is a potential point of intervention.”

Harnessing the potential of cross-disciplinary, interfamilial collaboration

Ari Molofsky specializes in immunology and was already studying the function of the immune signal IL-33 in other parts of the body. Once Anna Molofsky identified IL-33 as a gene expressed by astrocytes, the spouses decided to combine their expertise to analyze how the immune system communicates with the brain and potentially open new avenues of treatment for neurodevelopmental disorders.

“It's a bit of a natural collaboration because I've been a glial biologist for some time, and glial cells are some of the major actors in neuroimmune diseases,” said Anna Molofsky.

Microglia help regulate synaptic engulfment and pruning in the brain [Rendering courtesy Molofsky Lab]

She is curious to see if treatment with IL-33 or other immune proteins can make the brain more malleable in adults. Increasing neural plasticity may help with conditions linked to abnormal pruning, such as autism and schizophrenia. It may also be beneficial for patients with stroke or traumatic brain injury where the brain is forced to rewire to cope with the trauma.

“The brain is incredibly plastic, more plastic than we would think,” she explained. “Understanding how these developmental mechanisms exist in adulthood or can be coaxed into working to help the brain to remodel could potentially be beneficial for psychiatric diseases.”

“We hope that by better understanding the normal roles of the immune system the developing brain, we can better understand how it malfunctions in the context of disease,” added Ari Molofsky.

The study was supported by funding from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund, Larry L. Hillblom Foundation, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease, National Institute of Mental Health, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health New Innovator Program, National Science Foundation, and Pew Charitable Trusts.

Lead authors on the paper are Molofsky Lab members Ilia Vainchtein, PhD, and Gregory Chin. Other authors from UCSF Psychiatry include Kevin W. Kelley, John G. Miller, Elliot Chien, Phi Nguyen, Hiromi Inoue, and Leah Dorman. Key contributions were also made by collaborators Jeanne Paz, PhD, of the UCSF Department of Neurology and Gladstone Institutes of Neurological Disease; Frances S. Cho, of the UCSF Neuroscience Graduate Program and Gladstone Institutes of Neurological Disease; Shane Liddelow, PhD, and the late Ben Barres, MD, PhD, of Stanford University. Other authors include Omar Akil, PhD, of the UCSF Department of Otolaryngology and Satoru Joshita, of the Shinshu University School of Medicine.

Read the paper

About UCSF Psychiatry

The UCSF Department of Psychiatry and the Langley Porter Psychiatric Institute are among the nation's foremost resources in the fields of child, adolescent, adult, and geriatric mental health. Together they constitute one of the largest departments in the UCSF School of Medicine and the UCSF Weill Institute for Neurosciences, with a mission focused on research (basic, translational, clinical), teaching, patient care and public service.

UCSF Psychiatry conducts its clinical, educational and research efforts at a variety of locations in Northern California, including UCSF campuses at Parnassus Heights, Mission Bay and Laurel Heights, UCSF Medical Center, UCSF Benioff Children's Hospitals, Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital and Trauma Center, the San Francisco VA Health Care System and UCSF Fresno.

About the UCSF Weill Institute for Neurosciences

The UCSF Weill Institute for Neurosciences, established by the extraordinary generosity of Joan and Sanford I. "Sandy" Weill, brings together world-class researchers with top-ranked physicians to solve some of the most complex challenges in the human brain.

The UCSF Weill Institute leverages UCSF’s unrivaled bench-to-bedside excellence in the neurosciences. It unites three UCSF departments—Neurology, Psychiatry, and Neurological Surgery—that are highly esteemed for both patient care and research, as well as the Neuroscience Graduate Program, a cross-disciplinary alliance of nearly 100 UCSF faculty members from 15 basic-science departments, as well as the UCSF Institute for Neurodegenerative Diseases, a multidisciplinary research center focused on finding effective treatments for Alzheimer’s disease, frontotemporal dementia, Parkinson’s disease, and other neurodegenerative disorders.

About UCSF

UC San Francisco (UCSF) is a leading university dedicated to promoting health worldwide through advanced biomedical research, graduate-level education in the life sciences and health professions, and excellence in patient care. It includes top-ranked graduate schools of dentistry, medicine, nursing and pharmacy; a graduate division with nationally renowned programs in basic, biomedical, translational and population sciences; and a preeminent biomedical research enterprise. It also includes UCSF Health, which comprises top-ranked hospitals – UCSF Medical Center and UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospitals in San Francisco and Oakland – and other partner and affiliated hospitals and healthcare providers throughout the Bay Area.